Forget Excel: Automated Scraping of Prices, Reviews, and Trends for Market Analysis

Marketing intelligence has long moved beyond “manually checking a couple of prices.” In practice, you need to regularly collect hundreds or thousands of product listings: price, availability, shipping, discounts, reviews, and demand signals - and get more than just a table. You need clear conclusions: where a competitor is dumping prices, which products are seeing rising negativity, and which topics are “taking off.”

With modern libraries and cloud services, all of this can be automated quite easily. Let’s break it down.

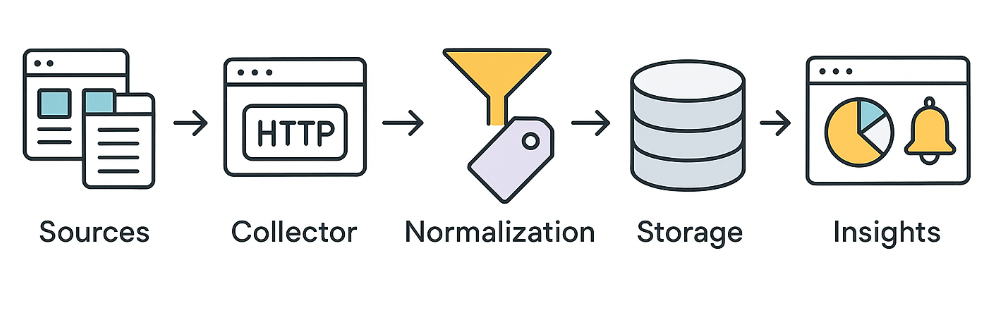

A simple baseline scenario

- We take a list of products or categories and set an update plan: once a day for basic monitoring, or once an hour for highly competitive niches.

- For each product page, we extract the “commercial fields”: price, currency, availability, shipping, discount, seller.

- We collect reviews: rating, text, date, helpfulness, and also problem signals (shipping, quality, warranty).

- We cross-check with trends: whether interest in the category/brand/model is growing, and whether that matches the dynamics of prices and reviews.

- We store everything and set up alerts: “price dropped by 7%,” “spike in shipping-related negativity,” “category is on the rise.”

Price scraping

Scraping prices from competitor sites or aggregators is a classic task. Most often, prices are present in static HTML (except for SPA applications). In simple cases, it’s enough to make a GET request with requests and parse the response with BeautifulSoup:

language

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = "https://example.com/product/123"

headers = {"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0"} # sometimes you need to spoof the User-Agent

res = requests.get(url, headers=headers)

soup = BeautifulSoup(res.text, 'html.parser')

price = soup.select_one(".product-price").text.strip()

print("Price:", price)This code will extract the price from the HTML page. Obviously, this is the ideal case - when there are no obstacles. In any case, it’s important to check whether elements exist and handle exceptions (in case of blocking or markup changes). And if prices are generated via JavaScript, you may additionally need page rendering.

- For periodic price checks, it’s convenient to iterate over product lists (

for page in category: ...). - Collected data can be stored in CSV/JSON or a database.

Which fields to store (so you don’t have to redo it later)

For prices, it helps to store not only the “price” itself, but also the context:

- the final price and the old price (if there is a discount);

- currency, unit (pcs/kg/l), VAT (if explicitly shown), shipping cost;

- availability (

in stock / out of stock / pre-order) and delivery time; - identifiers: URL, domain, SKU/article number (if available), product name;

- snapshot date and time, as well as the source (site/category/search results page).

This turns the process from “pulled a number” into a dataset you can use for proper comparisons and charts.

And for frequent requests, it’s better to distribute them across different proxies so you don’t exceed limits and run into blocks.

When requests is enough, and when you need rendering

requests + BeautifulSoup work great if:

- the price and required fields are present in the HTML immediately;

- there is no mandatory authentication;

- the site does not require an active session and does not throttle frequent requests.

You need browser rendering (Playwright/Selenium or a cloud browser) if:

- the HTML contains only a “shell,” and the data is pulled in via JS;

- content appears only after scrolling, clicking “show more,” applying filters;

- the page depends on geography, cookies, or session state.

Review scraping

Reviews of products/services are often published on product pages or on aggregators (Trustpilot, Google Reviews). Sometimes you can get this data as static HTML, but quite often reviews are loaded dynamically or require clicking a “more” button. The simplest approach - just like with prices - is to use requests + BeautifulSoup:

language

url = "https://example.com/product/123/reviews"

res = requests.get(url, headers={"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0"})

soup = BeautifulSoup(res.text, 'html.parser')

reviews = [rv.get_text(strip=True) for rv in soup.select(".review-text")]

print("Found reviews:", reviews)However, if the site loads reviews via JS (for example, on scroll or via an AJAX request), a static request won’t return the full list. In such cases, you can use browser automation - here’s an example with Playwright:

language

from playwright.sync_api import sync_playwright

with sync_playwright() as p:

browser = p.chromium.launch(headless=True)

page = browser.new_page()

page.goto("https://example.com/product/123/reviews")

# Wait for elements to appear, or scroll if needed

page.wait_for_selector(".review-text")

reviews = [el.inner_text().strip() for el in page.query_selector_all(".review-text")]

print("Reviews:", reviews)

browser.close()Playwright (and Selenium, by the way) renders JavaScript, so it reliably gets dynamically loaded content. However, such solutions are heavier and slower than a normal HTTP request. To collect a large volume of reviews, you may need serious infrastructure and proxy rotation.

Data quality matters more than it seems

Even if the scraper “collected something,” analytics can go off the rails because of small details. A minimal set of practices:

- Normalization: convert prices to a single currency, a single unit of measure, and a consistent number format; store price and shipping separately.

- Deduplication: the same product can appear under different URLs or from different sellers - so you need matching rules.

- Outlier checks: a sudden 60% price drop often means a selector error, a promo banner instead of a price, or a markup change.

- Completeness control: the share of empty prices/reviews per source is the simplest indicator that the site started “cutting off” your collection.

- Error logs: record response codes (403/429/5xx), timeouts, and retry frequency - this helps you quickly understand what exactly broke.

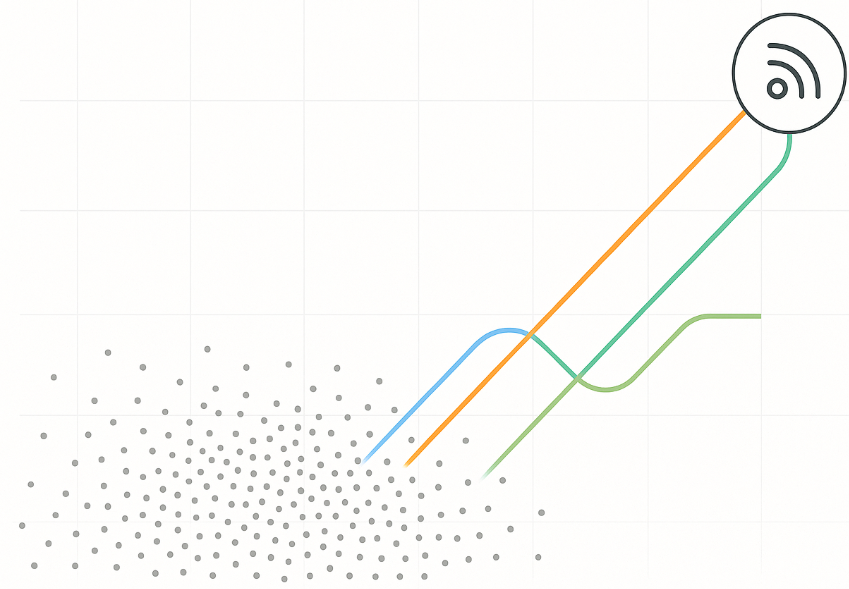

Trend scraping

Market trends are either search query statistics or popular products/topics. Trend sources can vary: Google Trends, social networks, analytics services. With the pytrends library, you can get Google trends:

language

from pytrends.request import TrendReq

pytrends = TrendReq(hl='ru-RU', tz=360)

trending = pytrends.trending_searches(pn='russia') # or 'world'

print(trending.head())If trends are presented on a dynamic page (for example, the Google Trends “trending searches” feed or social feeds), you can again use Playwright for rendering:

language

with sync_playwright() as p:

browser = p.chromium.launch(headless=True)

page = browser.new_page()

page.goto("https://trends.google.com/trends/trendingsearches/daily?geo=RU")

titles = [el.inner_text() for el in page.query_selector_all(".details-top > div.title")]

print("Trending searches:", titles)

browser.close()The idea is that any publicly available information can be obtained via scraping. Trends can also be pulled from APIs, but many people prefer collecting them directly from pages.

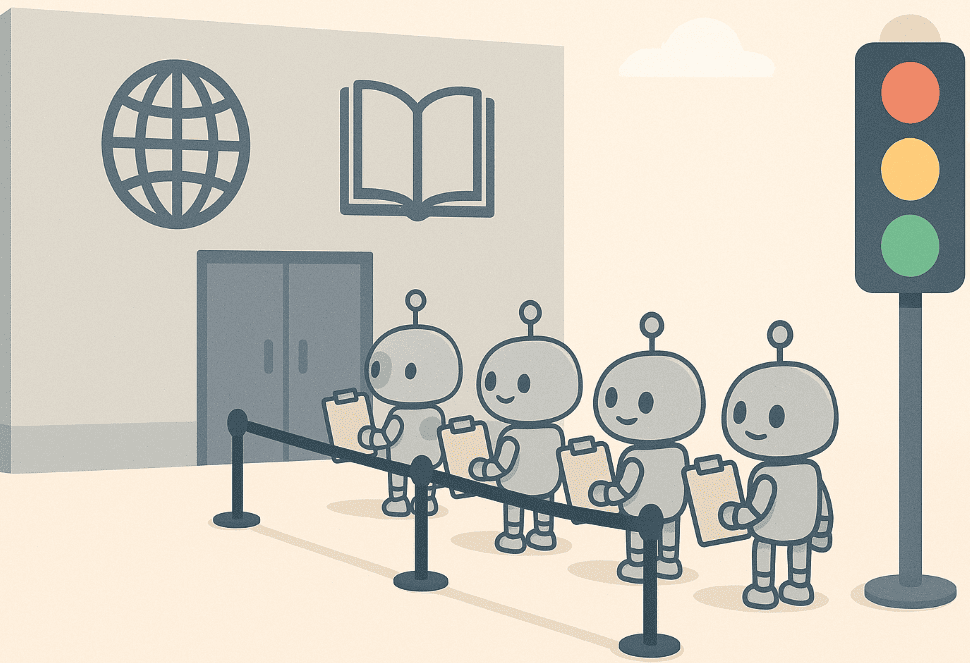

Sustainable collection of public data: constraints and practices

When collection becomes regular and large-scale, the main problem is not “how to parse HTML,” but how to make the process sustainable: so it runs for weeks, doesn’t break due to small changes, and doesn’t turn into constant manual maintenance.

Modern sites are often dynamic: part of the data is loaded via API after the page loads, the interface is re-rendered on the client, and the content depends on geography, cookies, and behavior. At the same time, many resources introduce protective mechanisms: request rate limits, checks of browser attributes, filtering of suspicious traffic, CAPTCHAs, and additional session checks.

The practical goal here is one: to collect publicly available data reliably, follow source rules, and avoid creating excessive load.

To reduce failures and make collection sustainable, people typically use a combination of practices:

- Rendering. A real browser (Selenium/Playwright) or a cloud browser API - Scrapeless has one - helps correctly fetch data from pages where content is generated by JavaScript and depends on session state.

- IP and geo rotation. Distributing requests across a pool of addresses helps you avoid hitting source limits and reduces the share of 429/403 during regular monitoring.

- Request management. Realistic headers, correct handling of cookies/sessions, timeouts, retries, and pauses between requests reduce “noise” and make behavior closer to that of a normal user.

- Availability checks. If a source introduces an additional check (for example, a CAPTCHA), handling it - CAPTCHA solving - must be part of the pipeline; otherwise, collection will fail in random spots.

- Cloud web collection APIs. Ready-made solutions take care of rendering, the network layer, retries, and the proxy layer so you can focus on data and analytics rather than infrastructure.

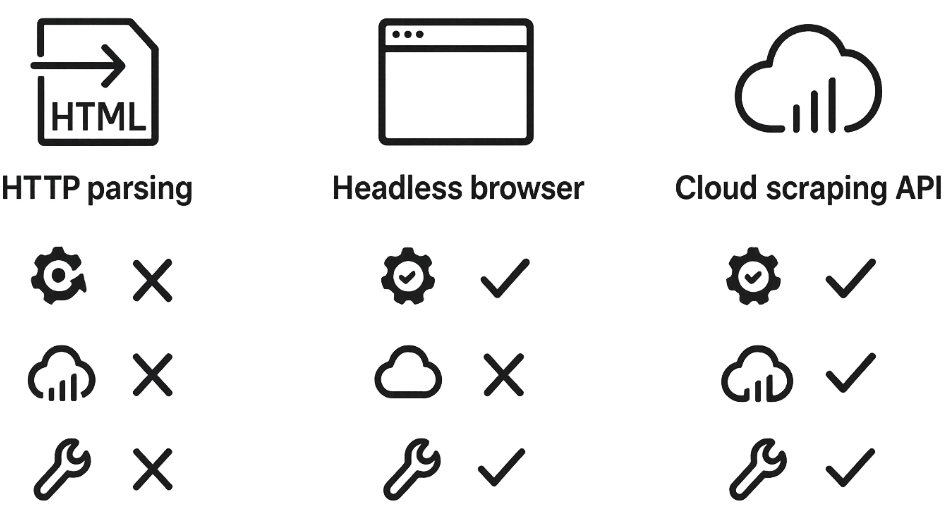

How to choose the right approach

- If the required data is visible in the raw HTML and the volume is small, start with

requests+ BeautifulSoup. It’s the fastest and easiest to maintain. - If the data appears only after JavaScript execution, clicks, or scrolling, use Playwright: it provides full page rendering and fits dynamic scenarios.

- If the task is limited by scale, stability, and infrastructure (many sources, lots of parallel requests, persistent blocking, CAPTCHAs, proxy pools, retries), it makes sense to move rendering and the network layer into the cloud.

When Scrapeless is recommended

- Scraping Browser is useful when you need a Playwright-style approach but don’t want to run and maintain your own browser farms.

- Universal Scraping API fits when you need stable responses for complex pages and want “request → result” without fine-tuning rendering.

- Additional components like proxies and CAPTCHA solving cover the network routine that typically consumes more time than the scraping itself.

Scraping tools: a comparison of popular solutions

Tool - Type - Dynamic JS - Proxy/anti-bot - Speed - Comment

requests + BS4 - HTTP library and HTML parser - No - No (manual setup required) - Very fast - Lightweight and simple; good for static pages, doesn’t handle JS

Scrapeless API - Cloud browser/scraping service - Yes (built-in) - Built-in IP rotation, CAPTCHA solving - Very fast - Cloud solution: renders JS, rotates IPs, solves CAPTCHAs automatically

Scrapy - Asynchronous scraper (Python) - No (needs Splash for JS) - Via middleware, requires setup - Fast - Scalable framework for large projects

Selenium - Browser automation - Yes - Configurable proxies - Slow - Universal (any JS), but resource-intensive

Playwright - Browser automation (newer) - Yes - Configurable proxies - Faster than Selenium - Faster, supports parallel contexts

PyTrends, APIs - Specialized APIs - No - Yes - Fast - Simplify tasks (Google Trends, etc.), but not general-purpose

Each tool has its pros and cons. Scrapy is great for batch scraping of static sites, Selenium/Playwright for full rendering, and Scrapeless and other cloud APIs when you want to address anti-bot challenges - when you need to reduce failures and take infrastructure work off the team (rendering, network retries, proxy layer, access-check handling).

Conclusions and recommendations

Scraping prices, reviews, and trends is an important tool for an analyst. For a simple starter project, requests and BeautifulSoup are enough: they’re easy to learn and fast on static pages. If pages are dynamic, add a browser-based approach (Selenium or Playwright). For serious projects, consider the Scrapy framework (it scales and has convenient “spider” APIs) or combine multiple approaches.

Dealing with anti-bot protections takes additional effort: proxies and rotation should be part of the infrastructure, and request headers should look “human.” It often makes sense to delegate these tasks to professional APIs (like Scrapeless) - they can handle CAPTCHAs and rotate IPs.

Step 1: pick 20–50 products and one source, collect price and availability fields, and store snapshots for 3–5 days. The goal is to verify that the data is stable and suitable for comparison.

Step 2: add reviews and set up a simple classification of issues by key themes (shipping, quality, warranty). Even at this stage, useful signals will appear.

Step 3: add trends for the category/brand so you understand where demand growth explains changes in prices and reviews.

Step 4: scale to the required volume, while adding data quality control (completeness, outliers, response codes) and alerts. This is cheaper than “fixing everything at the end” when the number of sources grows.

Final recommendations:

- Test the approach on a small volume before scaling.

- Use proxies to reduce the risk of blocking (especially for parallel requests).

- Follow scraping etiquette: slow down requests, use human-like headers, respect robots.txt at minimum.

- Track site changes - they may alter structure or strengthen protections.

- Consider cloud services to save time: they provide rendering and anti-bot handling “out of the box.”

In the end, thoughtful scraping allows you to extract valuable information for market decisions. By choosing the right tools and following the rules, an analyst can efficiently “dig out” insights from open data and avoid bans.